Cartography of the front lines

Advance and retreat in Europe

When war broke out in August 1914, the senior military commanders on both sides were equipped with strategic plans that had been years in the making.

On the Western Front, French offensives in Alsace and Lorraine (Map XVII) ended in failure. Meanwhile, the bulk of the German forces advanced through Belgium, as per the Schlieffen Plan. Their progress was halted by the Battle of the Marne, 6-9 September, and the front had stabilised by December, along a line running from the Swiss border to the North Sea.

On the Eastern Front, the Russians launched an attack on East Prussia on 18 August, but one of their armies was defeated at Tannenberg while the other was forced to retreat. They did, however, succeed in invading Galicia and halting the Turkish incursion into the Caucasus.

Finally, on the banks of the Danube the Serbs succeeded, against all expectations, in repelling the Austro-Hungarian forces and liberating Belgrade.

Within the space of four months, all of the strategic forecasts had proved to be entirely misjudged.

1914 L’offensive allemande sur le front Ouest

Starting on 7 August, the French forces launched attacks in Alsace, Lorraine and the Ardennes. All of these initiatives ended in failure: the French high command had underestimated the size and firepower of the German forces deployed to these sectors.

Meanwhile, further north, the great German offensive was already underway: the Germans swept through Belgium, in spite of the resistance they encountered at Liège (4-16 August). As the Belgians retreated towards Antwerp, the Germans began to threaten France’s northern border. The French and British forces were powerless to halt the German advance, losing key battles in the Sambre region (Battle of Charleroi), then at Cateau and Guise. The Germans cross the River Aisne, then the River Marne. Paris seemed to be within striking distance.

However, the pace of the advance had left the German infantry exhausted. On the French side, meanwhile, Chief of Staff General Joffre had learned lessons from the retreat and replaced many of his generals, as well as moving up fresh troops from the Vosges into the Champagne region. By September, the Allies were ready to launch a counter-offensive.

1914 La stabilisation du front Ouest

Amid the hills and ridges of the Vosges region, the frontline had stabilised by early September.

In Champagne, starting 6 September, the Allies attacked the Germans’ right flank and succeeded in breaking the line (First Battle of the Marne, 6-9 September). The Germans were forced to withdraw, digging in on the high ground overlooking the River Aisne, where they fortified with trenches. After some fruitless attempts to take these positions, the Allies dug trenches of their own.

To the north-west of Compiègne, the way was still clear. From 13 September onwards, the Allies and the Germans repeatedly attempted to outflank one another (the ‘Race to the Sea’). Battles in the Somme, Arras and Yser saw the front extended until it reached the North Sea.

By the end of 1914, the Germans and the Allies were deadlocked in opposing trenches along a front line which ran for some 750 kilometres. . In spite of repeated offensives from both sides, the Western Front remained locked in this static war of attrition until the Spring of 1918.

1915-1916 Stabilisation à l’Ouest, guerre de mouvement à l’Est

Throughout the year 1915, the German and Allied military commands both sought to regain the initiative on the Western Front. Brutal fighting in Ypres, Artois and Champagne yielded little in the way of results, apart from massive loss of life. The great battles of 1916, at Verdun and the Somme, also proved to be inconclusive in spite of the huge numbers of casualties sustained.

As well as deploying their own resources, the belligerents sought to expand their respective alliances in order to tip the balance of strength in their favour and break the deadlock. The Ottoman Empire (October 1914), Italy (May 1915), Bulgaria (October 1915) and Romania (August 1916) all joined the war.

The impact of these new alliances was only felt on the Eastern Front and in the Balkans. The Gallipoli landings attempted by the British, with troops from Australia and New Zealand (the Anzacs), was a costly failure; in Salonica, the Allies did not succeed in their attempts to open up a new front.

While the Italians and the Austro-Hungarians got bogged down in the Alps, Serbia and Romania buckled under the pressure from the Central Powers, while the Russians retreated over 400 kilometres despite not incurring any decisive defeats.

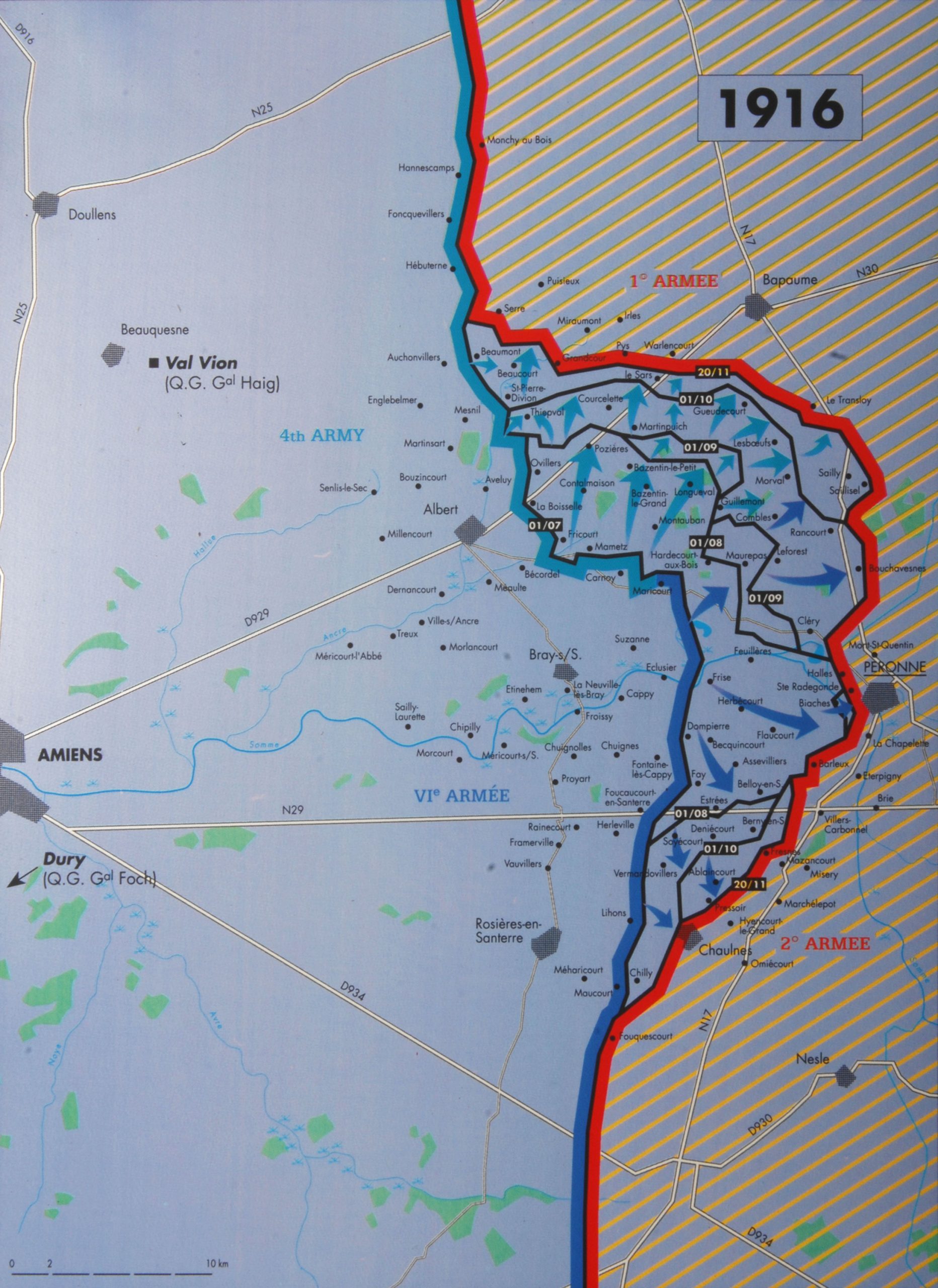

1916 Verdun et la Somme

Between the great clashes of 1915 and 1917, the Battle of Verdun and the Battle of the Somme offered a striking illustration of the failure of the Allies’ offensive strategies: a battle of attrition at Verdun, and a frontal assault on the Somme.

In December 1915, the Allies were busy preparing their campaigns for the following year. The generals were still determined to make a decisive break in the German lines. The Somme was selected as the principal theatre for these offensive operations. The great push forward in this sector was to be coordinated with allied offensives on the Russian and Italian fronts.

But on 21st February 1916 the Germans launched a ferocious attack on the front at Verdun. The fort of Douaumont fell on the 25th, followed by the fort at Vaux on 7 June. The French high command was obliged to rethink its plans: of the 330 infantry regiments at the generals’ disposal, 259 would see action at Verdun at one time or another. From August onwards the Germans were driven back, abandoning some of the territory they had won in the spring.

In the meantime, the Allied offensive on the Somme had forced the Germans to split their forces. Less substantial than had originally been intended, this offensive was principally led by the British and their imperial allies. Between July and November, they tried unsuccessfully to break through the German defences. They did succeed in retaking around fifty villages, but at horrendous cost: on just the first day on the Somme, some 60,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded.

This was the bloodiest day of the entire First World War.

At Verdun, the combined death toll from both sides was over 700,000. For the Somme, the figure was over 1 million. And yet the front line advanced by just a few miles.

Europe in 1917

The first months of 1917 were remarkable not so much for the military events they witnessed, but more for the growing sense of exhaustion within the warring parties and the crises this engendered.

In March, Russia’s royal regime collapsed; the revolutionary government which replaced the Tsar initially attempted to continue the war, but the Central Powers continued to make limited gains. When the Bolsheviks seized power in November, the situation changed dramatically: the new regime agreed an armistice with Germany in December later formalised in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

Just a few weeks previously, the Italians had suffered a catastrophic defeat at Caporetto. Nevertheless, the German and Austrian forces were unable to advance beyond the River Piave.

On the Western Front, the German forces fell back on the Hindenburg Line and withstood Allied offensives at the Chemin des Dames and Ypres.

The Western Front 1917

Acutely aware of the difficulties involved in holding a front line some 750 kilometres long, and at considerable distance from his supply bases, Hindenburg, the new commander-in-chief of the German forces, along with his deputy Ludendorff, decided to pull their forces back behind a carefully-fortified defensive line known as the Hindenburg Line. This strategic retreat left the Allies to retake possession of a region which had been utterly devastated by years of fighting.

In April, French commander Nivelle launched a new offensive on Chemin des Dames. As in the preceding two years of campaigning, the loss of life incurred in this offensive was enormous compared with the territory recaptured. Nivelle was soon replaced by Pétain, , whose first task was to get a handle on the mutinies triggered by the failure of the offensive. Pétain calmed this unrest with a combination of limited repression and improvements to the soldiers’ living conditions.

As for the British sections of the line, the Battle of Passchendaele (also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, July-November 1917), fought in the gruelling mud of Flanders, did not result in any significant breakthrough.

The German Spring Offensive of 1918

In order to catch the Allies by surprise, the German commanders opted to eschew the usual preparatory artillery battering. Instead of a mass offensive, they attempted to punch through the lines with mobile units which could then be used to outflank the allied forces. The attack was aimed at the point where the French and British sections of the line met, in an attempt to drive a wedge between the Allies.

The main thrust of the offensive began on 21 March, between Arras and La Fère where, for the first time since 1914, the Germans succeeding in moving the front line by a meaningful distance. The Allies retreated hastily, but were able to halt the German advance at Montdidier. A secondary offensive was launched at Ypres in April, but the German offensive really got going in Champagne in late May. The invaders recrossed the Marne, and Paris was in danger once again.

However, by this time the German army was exhausted and unable to supply reinforcements. This last-gasp offensive was definitively halted between 15th and 17th July, at the Second Battle of the Marne.

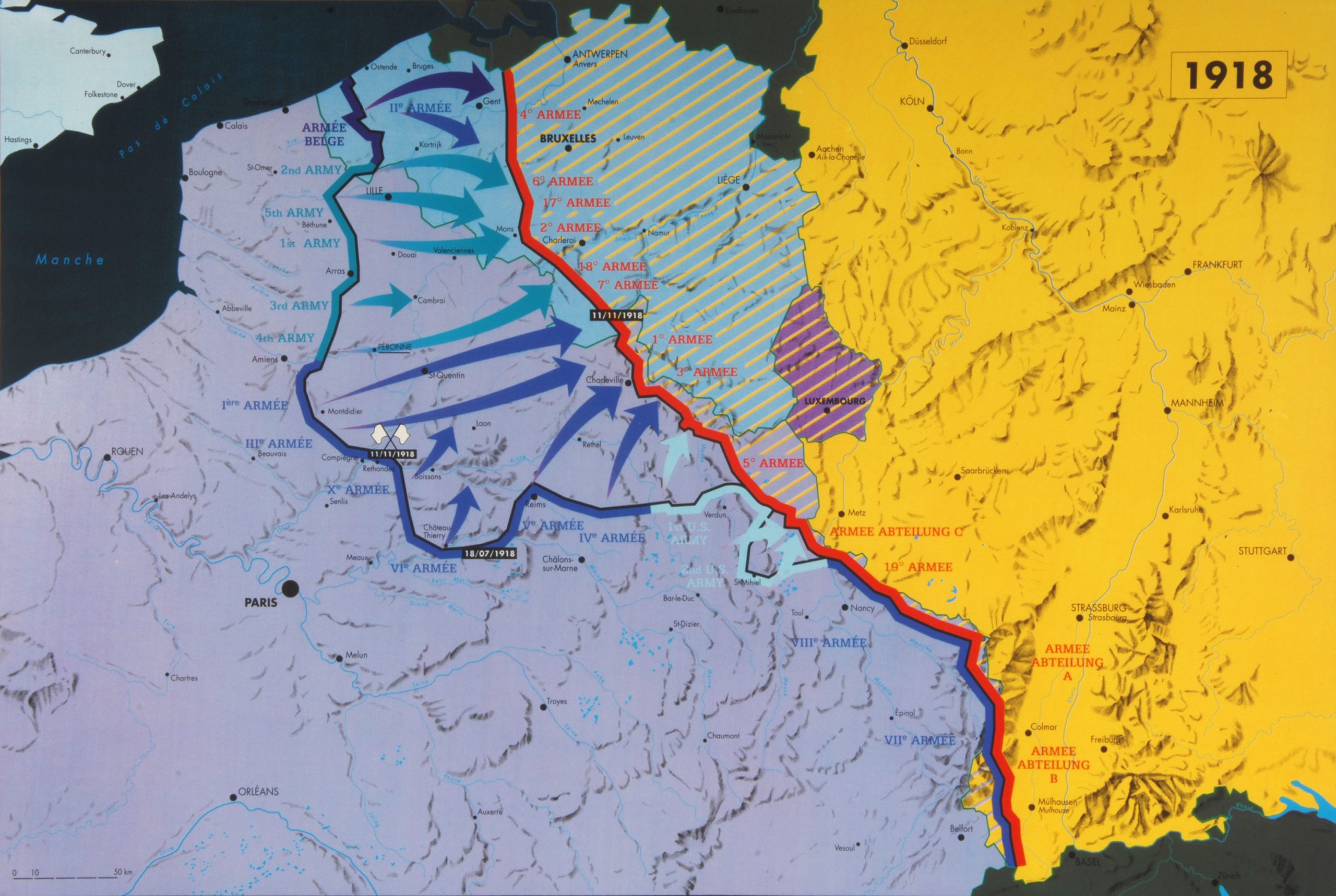

1918 La contre-offensive des Alliés

By 18th July the Allies were in a position to launch their counter-offensive. The pocket of resistance at Château-Thierry was gradually recaptured, with the Americans playing a prominent role. The Allies were increasingly confident of their superiority in terms of both materiel (tanks, aeroplanes, artillery) and manpower. In August, the British launched a new offensive on the Somme. In September, the Americans followed suit at Saint-Mihiel.

Although there was no catastrophic defeat to speak of, with each of these offensives the German army was forced to retreat and the Allies captured large numbers of prisoners. The German retreat was orderly, but morale among the troops was at rock bottom. Continuing the war any further could only end in disaster.

By the time the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, two days after the abdication of Wilhelm II, virtually all of France’s national territory had already been liberated from the German occupying forces.

German victory in the East

The collapse of Russia opened up new perspectives. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) saw Russia abandon all of her westernmost provinces, from Ukraine to Finland. Occupying these territories immobilised some of the military capacities of the Central Powers, but it also meant that the war now hinged almost entirely upon the Western Front.

The arrival of large numbers of American troops, from March 1918 onwards, tipped the balance of power in the Allies’ favour. Germany needed to launch an offensive immediately.

1918 L’effondrement des Puissances Centrales

The German Spring Offensive of 1918 ended in failure; the Austro-Hungarian forces endured a similar reversal of fortunes on the Italian front. The war fatigue which had ended Russia’s involvement in the conflict in 1917 was now taking hold of the Central Powers: military defeats and internal crises went hand-in-hand.

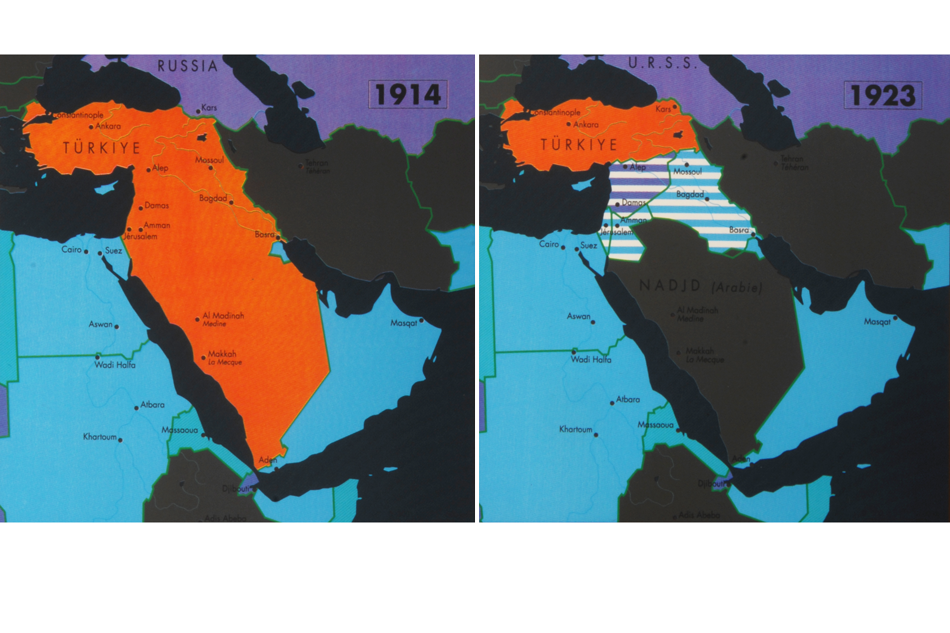

The Allies launched a new offensive in the Balkans on 15 September, then in Italy on 24 October. After the collapse of Bulgaria, the Austro-Hungarian army was in disarray as different national groups within the empire began to declare independence. The Ottomans, meanwhile, were under pressure following the Allied victory in the Balkans and the rapid advance of British troops into the Middle East.

A wave of armistice agreements were signed: 29 September with Bulgaria, 30 October with Turkey, 3 November with Austria, 11 November with Germany and finally, on 13 November, with Hungary.

The end of the war

Between 1914 and 1923, Europe, the Middle East and Europe’s colonial empires were all dramatically reshaped by treaties signed in and around Paris (including the Treaty of Versailles), as well as numerous treaties settling localised conflicts.

Germany renounced its claims on Poznan, Alsace and Lorraine. The victors occupied the Rhineland, which became a demilitarised zone, while France also claimed ownership of the coalmines of Saarland for a period of 15 years.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire disappeared and Soviet Russia, excluded from the negotiations, lost its western provinces. Central and Eastern Europe were now divided into a mosaic of fledgling nation states, including Poland and Czechoslovakia, separating Russia from the rest of Europe.

The Ottoman Empire was shorn of its possessions in the Arab world, for which the League of Nations established British and French Mandates.

Unsolved problems

Germany was held responsible for the war, and as such was forced to accept new borders which left many German-speaking people outside the frontiers of the Reich (Gdańsk, East Prussia, Sudetenland, Austria), along with limits to her sovereignty and severely depleted military capabilities.

The Italians, meanwhile, felt insufficiently rewarded for their involvement in the war.

The question of what to do with national minorities was not entirely settled. Most countries had outstanding claims to the territory of their neighbours (Hungary wanted Transylvania back, on account of the sizeable Magyar population), or else were riven by serious internal tensions (e.g. between Serbs and Croats in Yugoslavia).

In the Middle East, Arab nationalists rejected the French and British mandates as well as the expansion of the Jewish community in Palestine, actively encouraged by the British.