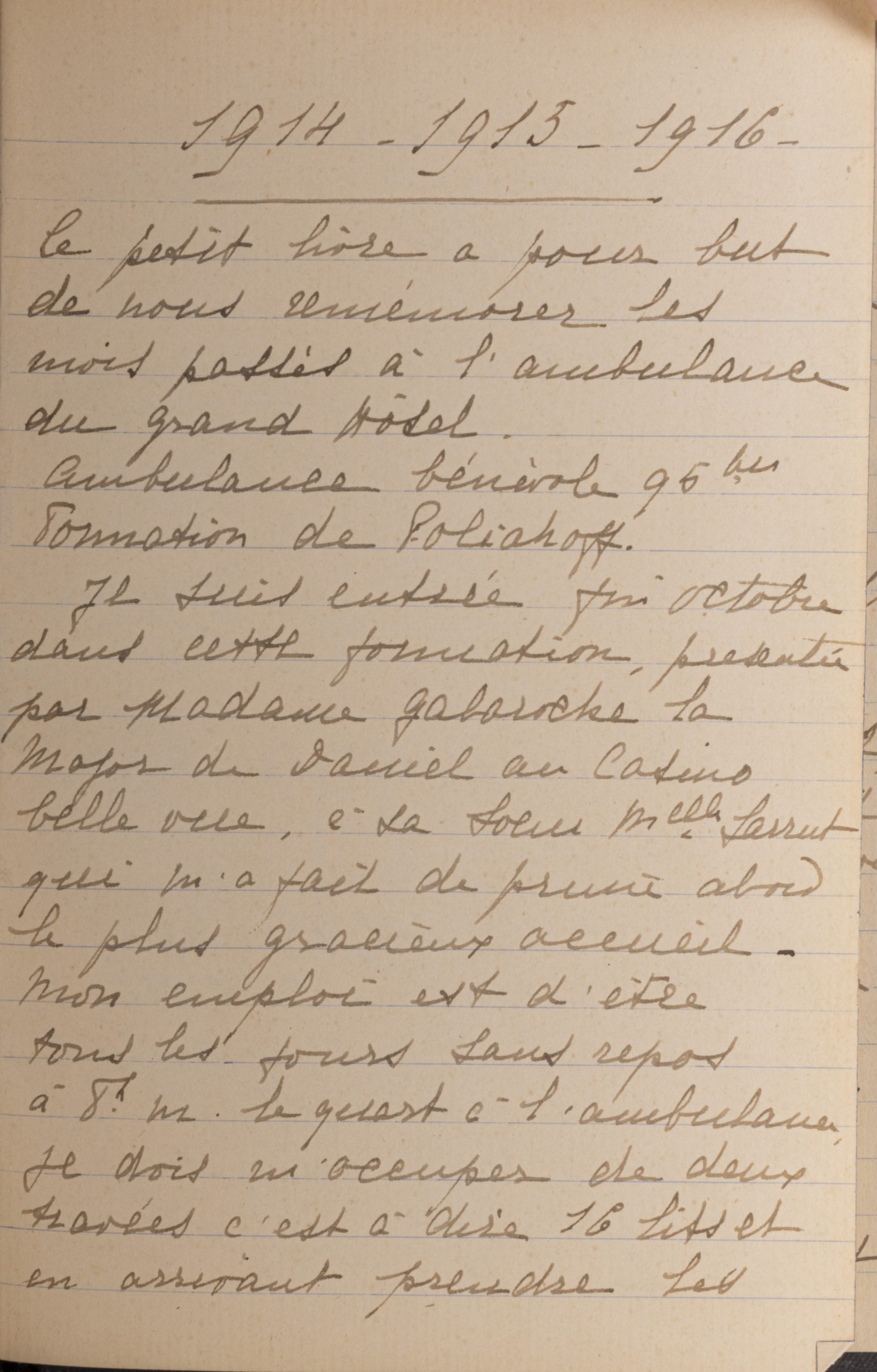

A handwritten testimony

An exceptional, unpublished first-hand account from the collections of the Historial of the Great War: a handwritten testimony from Geneviève Letrosne, nurse at Volunteer Hospital 95bis in Biarritz, 1914-1916

Invphys. 73287 – 175 x 117 mm. Collection Historial de la Grande Guerre

Donated by descendants of Geneviève Letrosne in 2017, along with a photo album featuring images from Volunteer Hospital 95bis.

A first-hand account written by a nurse who treated wounded soldiers in 1914-1918 is a rare and precious find. It offers an insight into the many and varied ways in which wounded soldiers suffered the consequences of war, and the devotion of the “angels in white” working at hospitals away from the front.

From the front to the rear, evacuating the wounded

In France, some 4.266 million men were wounded during the war, around half of all the soldiers in action (8.5 million). This unprecedented rate of injury can be attributed to the devastating impact of heavy artillery. For the army medical corps, evacuating the wounded was a top priority. The patients then needed to be sorted into categories based on the nature of their injuries, and operated on as soon as possible. Considerable progress was made, not least thanks to the development of radiography and the use of the Dakin-Carrel method of antiseptic treatment in order to stop the spread of gangrene. Regimental medical facilities near the front line provided first aid and transportation by stretcher-bearers, organising evacuations for different categories of wounded. Intermediary hospitals – or hôpitaux d’origine d’étapes – were located near key railway hubs, taking care of evacuated soldiers en route for medical institutions away from the front, namely:

1) permanent military, civilian or combined hospitals

2) temporary hospitals: additional hospitals (HC); auxiliary hospitals (HA) and volunteer hospitals (HB). Volunteer hospitals were generally named after the charitable societies which operated them: for three years, they were entirely funded by these private resources.

Volunteer hospital No. 95 bis, Biarritz

On 29 October 1914, Mme Geneviève Letrosne joined volunteer hospital 95bis, operated by Dr. Poliakoff and occupying the Grand Hôtel de Biarritz. In this notebook she neglects to mention whether she had chosen this particular hospital of her own accord, or if she was simply posted here after undergoing training on site. Sixteen of Biarritz’s hotels were transformed into hospitals for the duration of the war, making the seaside resort one of the biggest medical centres on the Basque coast. Over a period of 18 months between late October 1914 and August 1916, Letrosne treated 1200 patients of all kinds, and from all backgrounds. She appears to have received accelerated training from the Red Cross before taking up her nurse’s uniform: blouse and apron, blue headscarf and cape when out and about. From the very first day she was expected to clean and dress the men, take their temperatures, serve lunch and change their dressings, all for a ward of sixteen beds. The very first dressing she had to change gave her an immediate insight into the seriousness of the wounds she would encounter, this one caused by a bullet passing through the thigh of a soldier: “the bone was broken, he was suffering and crying out pitifully (…) the pus was flowing…” Also enrolled at the hospital were her husband Charles Letrosne (1868-1939) an architect who would achieve considerable renown in the 1920s and 1930s, not least thanks to his well-regarded book on post-war reconstruction (Murs et toits sur les pays de chez nous, 1923/24/25)nd their son Daniel, who would also go on to become an architect, and who was called up in 1916. Charles specialised in disposing of amputated limbs and sterilising surgical instruments, while Daniel took temperatures and changed dressings, as well as working as a medical secretary. Geneviève Letrosne later took charge of the patients’ wardrobe department: they generally arrived filthy and crawling with lice, and their personal effects needed to be treated accordingly. She also looked after the reserve stores (of basins, soap, towels etc.) and the laundry. She took up massage training in September 1915, and ended up giving twenty-nine or thirty massages in a single morning.

Medical care

When they arrived from the train, the wounded men were often dirty and had not had their bandages changed for four days. The author cites one exceptional case in which a Breton soldier arrived without any socks, claiming not to have washed for a year. He required a good brushing. If a big wave of patients arrived, there might be as many as ten or twelve operations performed in a single morning, followed by a further batch in the afternoon. The operating theatre shown in the accompanying photographs is large and well-lit. It featured all the “latest inventions:” an electro-magnet, and electro-vibration unit, a sterilizer and all the necessary surgical instruments in a glass case.

The first operation with which Geneviève Letrosne was involved was a blood transfusion, a common procedure during the war, but most of the surgeries involved amputations. She readily admits that, without the benefit of anaesthetic or cocaine, extracting projectiles from the wounded was difficult for her to stomach… She describes wounds afflicting every part of the body, as well as the damage wrought by shell shrapnel, exploding bullets and even nails. The most serious case involved a man severely wounded to the face, who died of blood loss. She describes the different reactions of patients waking up after their operations: sermons, prayers, lashing out…

The hospital had a fully stocked pharmacy, and an X-ray room which was well-installed and much used. G. Letrosne mentions some particularly useful tools, such as a “stereoscope which allows us to determine, by looking at the images in relief, the depth of an embedded projectile”, and the Hirtz compass which makes it “impossible to go wrong” when looking for a bullet or piece of shrapnel. She also mentions: radioscopy, mechanotherapy (an agreeable room also used for massages); three “mechano” exercise machines, a static bicycle, instruments for wrist exercises, a warm air and electrotherapy room, electrodiagnostics, a workroom and linen closets.

The hospital was thus equipped with all the latest technology, allowing the staff to care for the patients in the best possible conditions: of the thousand or so men treated here, “we only lost around a dozen.”

Carers

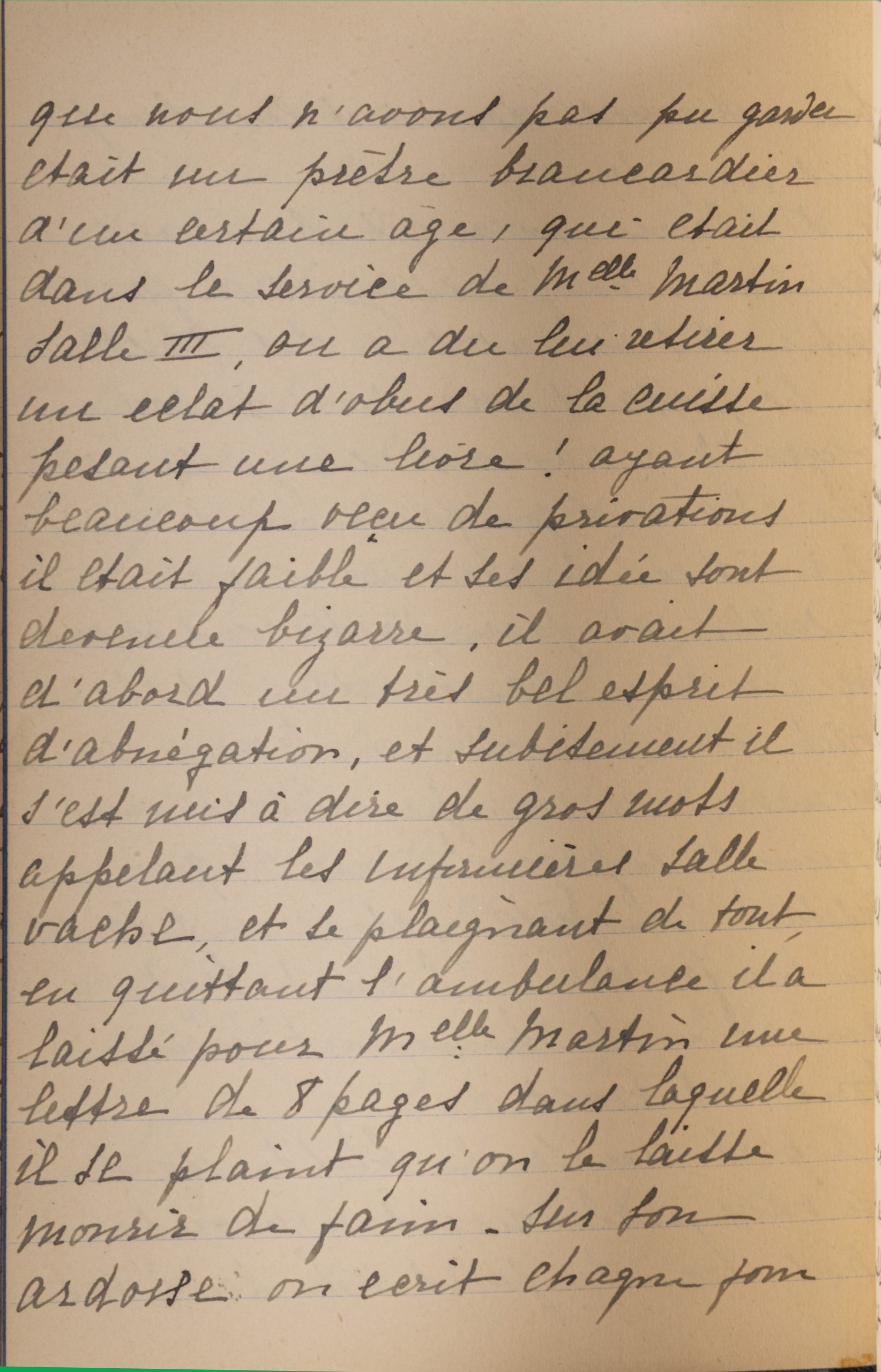

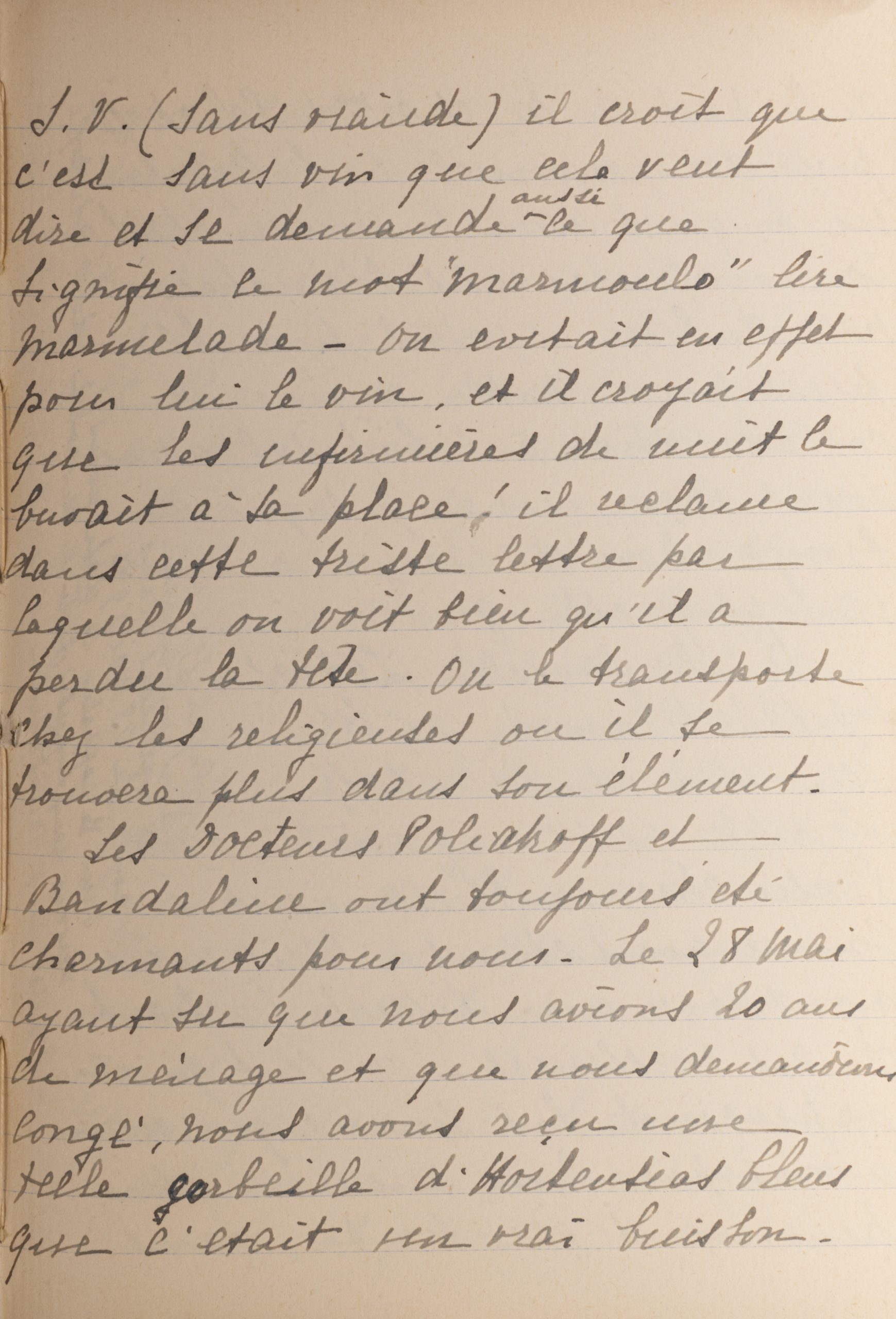

Geneviève Latrosne mentions doctors including Poliakoff, Bandaline (?) and Blanco, expressing her admiration for their diagnostic abilities and skills in the operating theatre. Among the nursing staff she mentions a few difficult characters, but all in all her descriptions are sympathetic. She also mentions two pharmacists, a director, a manager and two male nurses, one of whom was lazy and needed to be kept in line. Among her colleagues were a baroness, a countess, a Russian widow of ill repute and a young woman of questionable morals: all levels of French society were represented, but for the most part the volunteers were bourgeois women. A few of them developed feelings for patients.

The wounded

As a nurse, she enjoyed speaking with the wounded men with a steady blend of compassion and realism. She found the “negroes” to be polite, clean, “healthy and not prone to drinking.” One of these Senegalese soldiers carried with him various totems, including some sort of cow’s tail. One very tall Algerian (around 6’5”) with a wounded lung called her “maman confiture” and professed his love. There was also a patient from Reunion Island, who could not read and had thus not received any news from his family for two years. He loved the nurse like a mother, and presented her with a present when he was discharged.

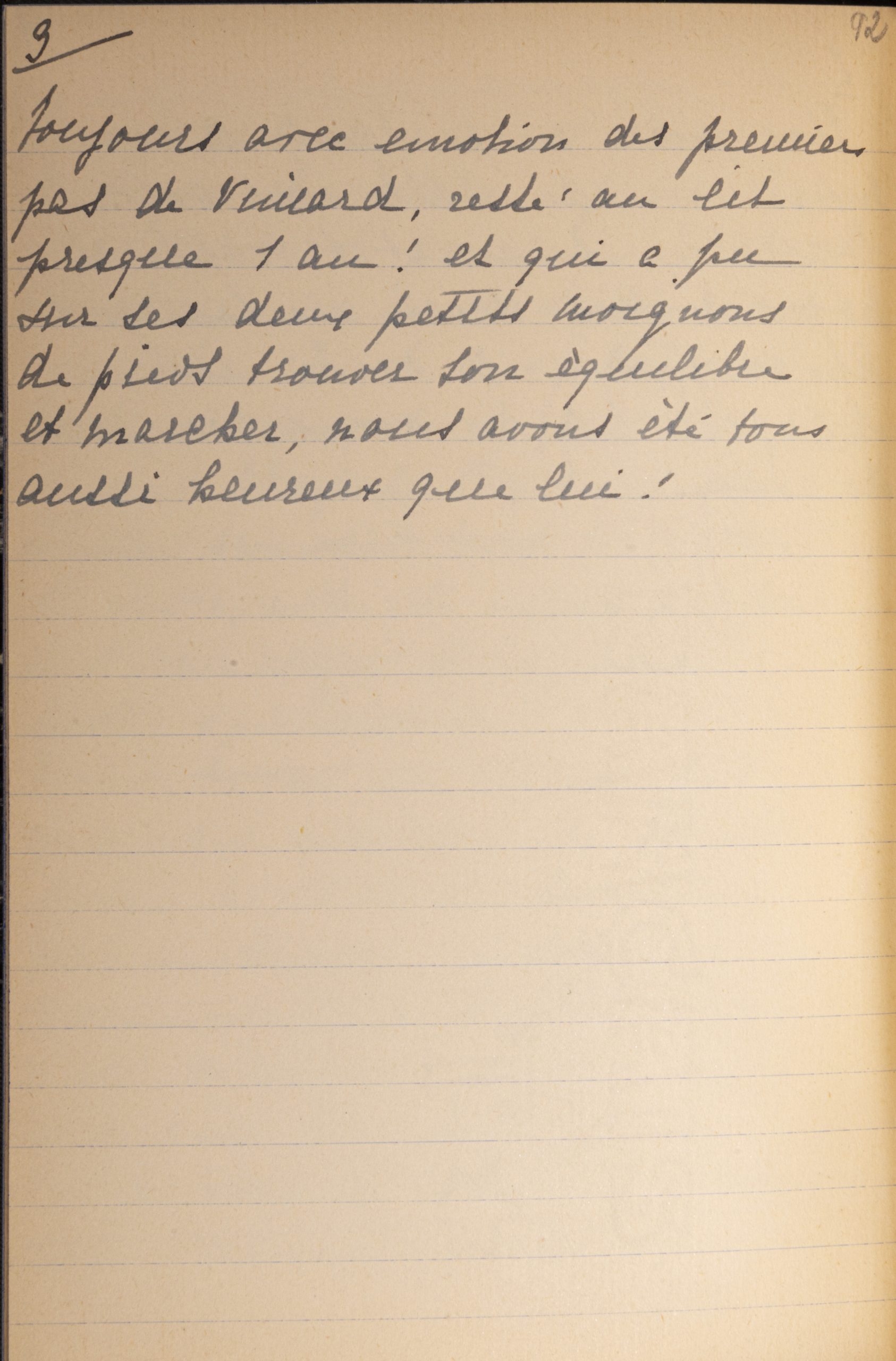

Descriptions of these wounded men take up much space in this notebook, as much for the care that they required as for the sympathy that Geneviève Letrosne felt for them. She regarded them as being generally decent fellows: “above all, the wounded soldiers are polite and well-behaved boys, they know very well what that have to do.” Only one patient did not take to her, and the dislike was mutual; Geneviève complains of his grumbling and inappropriate words. Among the patients she describes we find: one man who was wounded three times, and sent to Biarritz each time; one named Lalu who was “a bit simple” and followed here round; a Breton of 20 who did not speak French and whose cries of pain were “bestial” (“Oh me leg: me not transported; me cut leg!”). She also mentions a mad priest who kept complaining that he was starving to death, and a drunkard who would drink the 90° proof alcohol used to disinfect the thermometers. She was especially fond of certain patients, for example a Normandy lad by the name of Vinard who had frostbite in his feet and would be disabled for life. He was able to pay for special orthopaedic boots by making cotton bags and selling them, at Geneviève’s encouragement. While she doted on favourite patients like Vinard, nurse Letrosne was also particularly kind to patients from the occupied regions who were penniless and without news from their families. Death is mentioned relatively rarely in her account: one man from the Ile d’Oléron dies of gangrene before his family are able to visit, another man passes away while his wife appears to be more concerned about the fate of her horse, which is also on its last legs…

Life at the hospital

Geneviève Letrosne also describes moments of relaxation, including concerts (serious music and comic songs) and festive celebrations: Christmas trees with presents for the patients (she herself handed out postcards to all of the patients and nurses). On her 20th wedding anniversary, they all chipped in to buy her flowers. She appears to have been particularly generous when she first started at the hospital, giving out folding screens, tablecloths, soap, sponges, toothbrushes, soap boxes, aftershave, toothpaste, thermometers and even handkerchiefs, woollen blankets and rubber mats for the beds… Reading her notebook, it seems that she took great delight in giving presents whenever possible. Her photographs depict moments of shared happiness, without necessarily seeking to trumpet her own generosity. She was often moved by the departure of convalescents she associates with “children,” without making clear whether or not she means her own. Her working days began at 07:45 and often went on until 20:00, and sometimes she barely stopped for lunch. She was happy to give her time in this manner, and was not looking for recognition. She writes that she prefers not to wear her nurse’s uniform when out and about in town, in spite of the prestige attached to it.

Conclusion

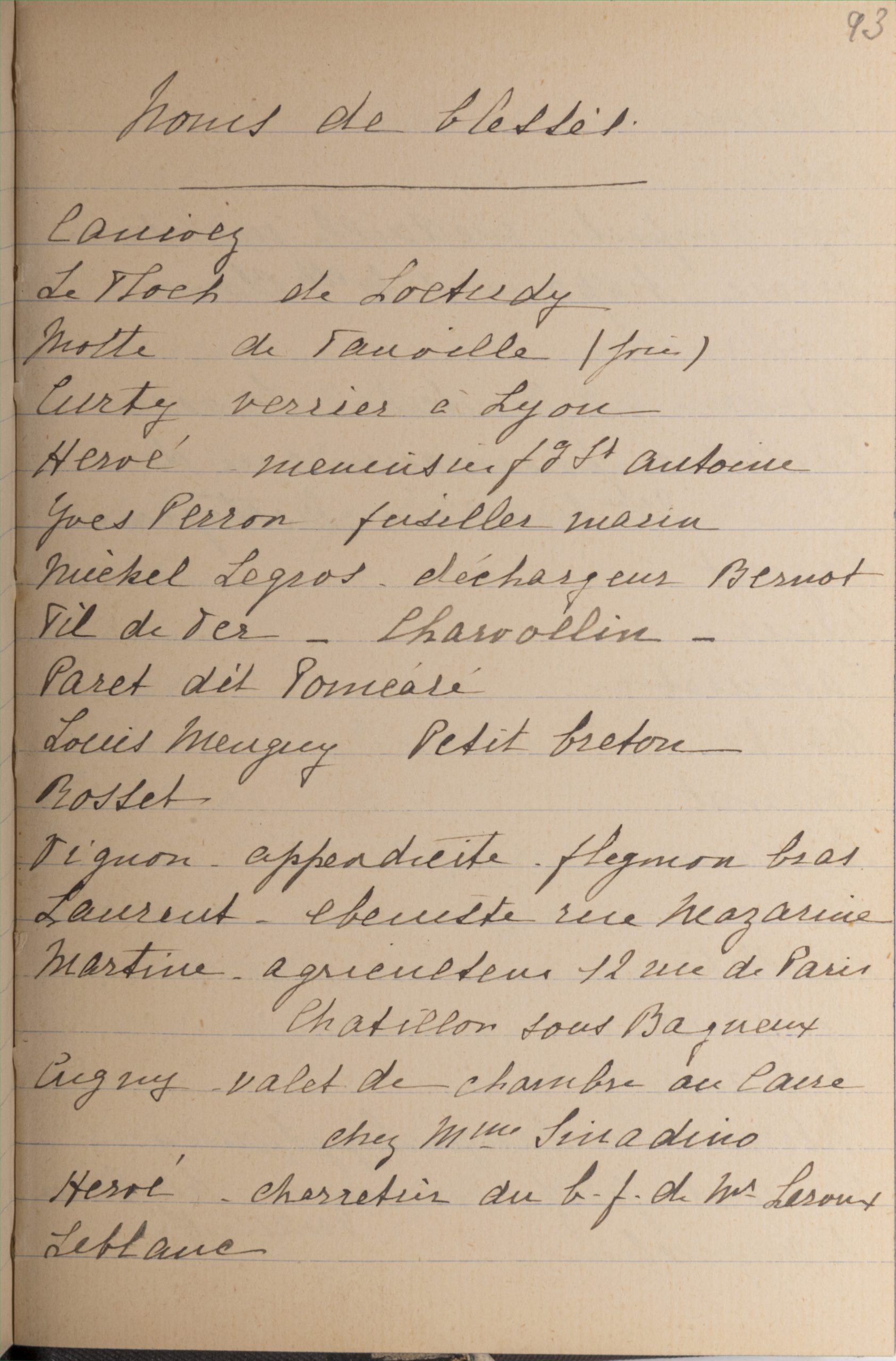

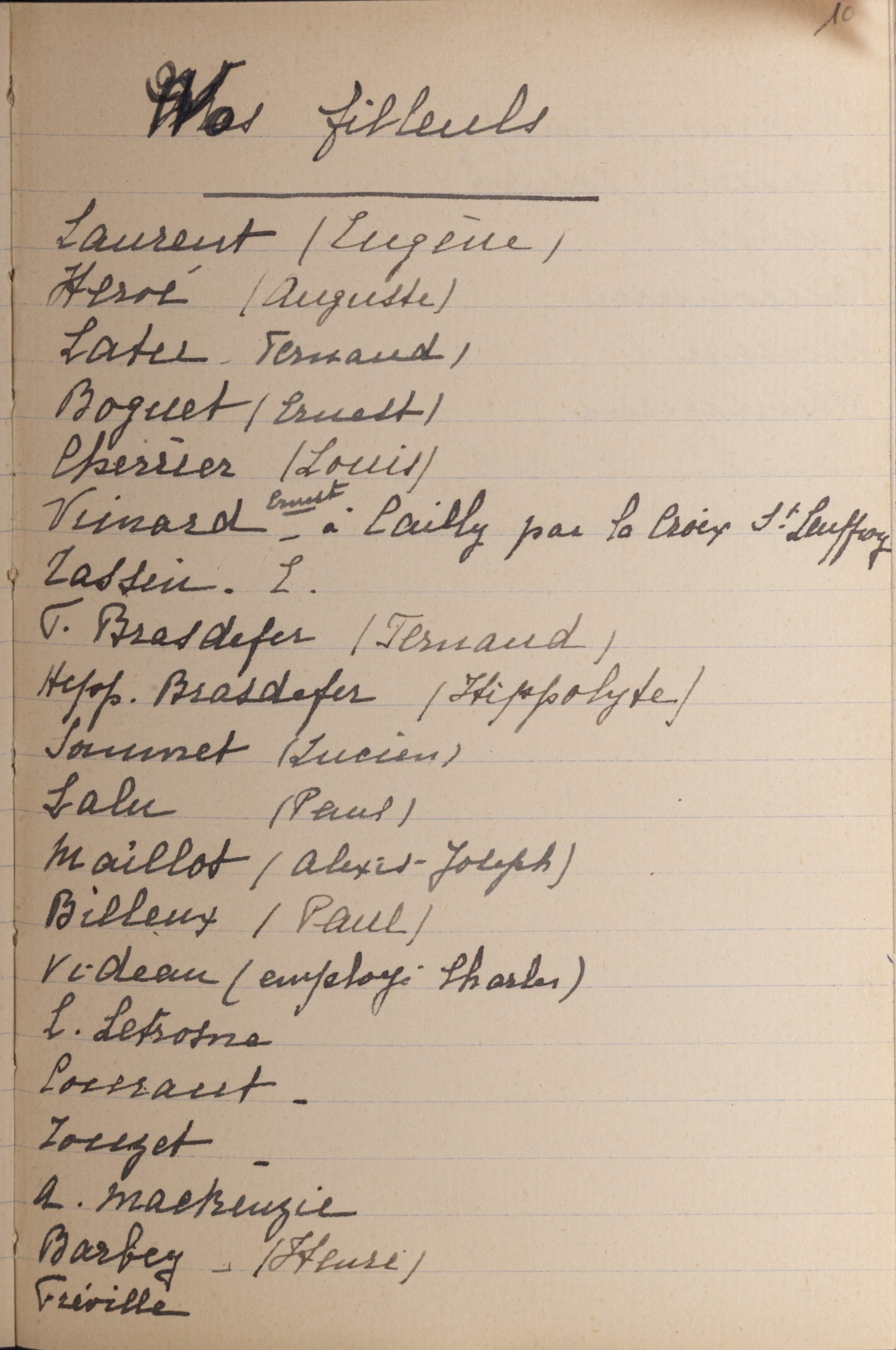

Geneviève Letrosne’s attachment to her patient is evident from the list of names which features at the end of the notebook: around one hundred and thirty men for whom she cared, and a list of twenty-eight “godsons” – her favourites, perhaps – with whom she kept in touch after they were discharged. Geneviève Letrosne, her husband and their son left the Grand Hôtel in October 1915, a departure which was celebrated with pomp and presents. They were presented with a plaque reading “To the Letrosne family, Poliakoff Volunteer Hospital 95bis, 29 October 1914-29 October 1915,” along with a Red Cross brooch. They also received many presents from the patients themselves: items hand-made by the men (a vase, a cotton bag, a raffia basket, a face mask), military objects (plate, canteen, cutlery) and even a war trophy (German tent pegs). After twenty months of this work, her husband suffered an intoxication as a result of the “repeated absorption of ether and chloroform.” She, too, was exhausted. The fact that their son Daniel had been called up to fight also precipitated their departure. Happy with her work, and with no regrets, Geneviève Letrosne continued to receive letters from many of the men she had treated.

In conclusion, she confides her sense of having done her duty: “What horrors we saw, but also what selflessness and what fine examples of the admirable French character.” Like so many volunteer nurses during the Great War, Geneviève Letrosne had learned a new profession She also left us this invaluable testimony, written with great clarity, realism and the occasional flash of humour. She probably wrote down these reflections in late 1915, so as not to forget her beloved patients and so that she could hand down to her son a detailed account of this hospital experience, at once an individual exploit and a collaborative enterprise for them as a family. As a volunteer nurse, she appears to have embodied the exact virtues expected of French women in wartime, a combination of patriotism and devotion.